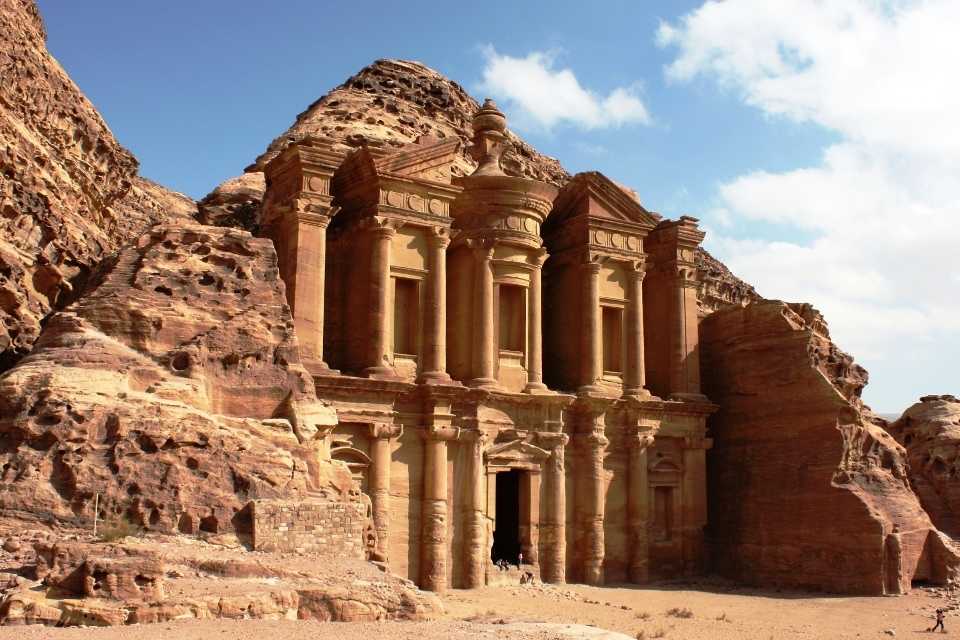

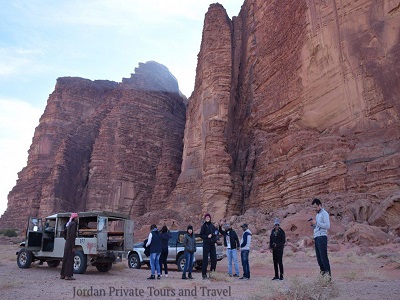

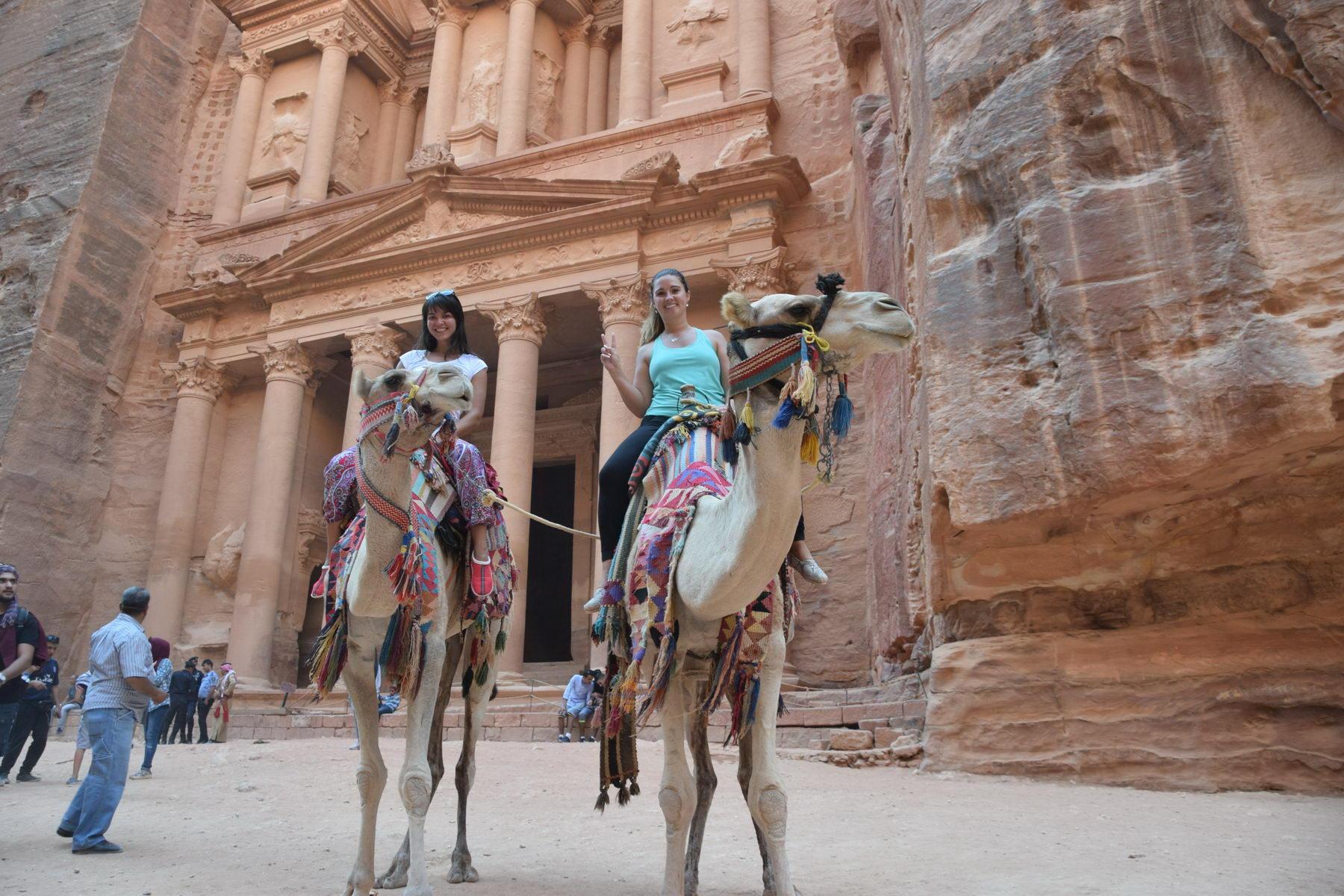

This is one of the most affordable tourism offers in Jordan, where we will visit 3 wonderful places and passing through amazing roads in Two-Days Trip... Starting from Amman toward Petra, and move afterwards toward Wadi Rum, Spend the night, discover the valley next day and move toward the Dead Sea. This tour comes with different versions : Private or small group tour, Guided or un-guided tour, so read carefully and book below what version you prefer (some days might not be available)